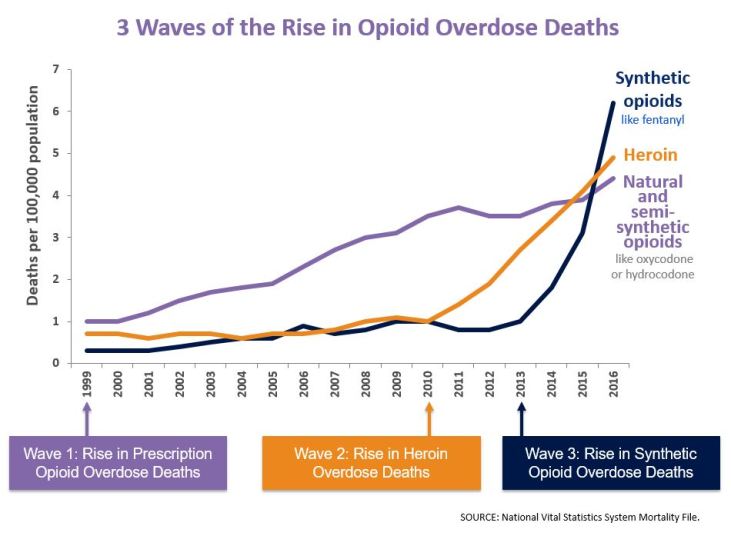

We are now in the third wave of America’s current opioid epidemic. The first wave began in the late 1990s. That’s when overdose deaths from prescription opioids began to rise. We decided to introduce abuse-deterrent Oxycontin® to try to reverse the course. We made it harder to abuse prescription drugs. Many people switched to heroin. The second wave of overdose deaths followed. The third wave started when illicitly manufactured fentanyl found a way into our drug supply. Fentanyl and its chemical sisters (called ‘analogs’) are not the primary drivers of opioid overdose deaths in the US.

Fentanyl is about 50 times more potent than heroin and about 100 times more potent than morphine. Just a 0.25mg of the stuff can kill a person. How much is a quarter of a milligram? As an article on CNN described a while ago, if you take a baby aspirin tablet — which is 81 mg — and divide it into 324 equal parts, each one of those parts would be a quarter of a milligram.

Slight changes to fentanyl’s chemical structure produce new designer opioids; many are just as potent as fentanyl. Because they are unique compounds, our legal system struggles to stay ahead of them. We make one illegal, and the chemists make a different one. For example, when acetyl fentanyl was made illegal in 2015, chemists make slight changes to the molecule to produce new drugs, chemical sisters, that do mostly the same thing. Some fentanyl analogs — such as carfentanil — are even more potent than fentanyl. Carfentanil is believed to be 100 times as potent as fentanyl.

The bulk of the current flow of Fentanyl comes by mail from China. While China has responded to US pleas to ban identified fentanyl analogs, innovative chemist-dealers continuously stay ahead of such bans by churning out new analogs. China, which does not have an opioid epidemic, is not as quick to respond to the call for banning new synthetic opioids as we would like. The relationship between China and opioids goes almost 200 years ago.

The Opium Wars are the beginning of modern Chinese history. Britain became a colonizing empire from a small island nation partly based on the access to new resources it had from North America. By the 18th century, it was trading around the world. It had a huge trade imbalance with China, buying porcelain, silk, and tea from there but being unable to sell much to it. The British East India Company, the same company that initially colonized India, began selling Indian opium to the Chinese. Opium use had been illegal in China since 1729. Yet the opium trade by the British, but also involving many American traders, led to many Chinese becoming addicted to China.

China decided to take action, and in 1839, seized over two and a half million pounds of British and American opium and destroyed it. The First Opium War between Britain and China followed. China lost badly. It signed the Treaty of Nanking (1842). Under the treaty, China gave up Hong Kong to Britain, and reluctantly opened up five ports to foreign merchants.

In 1844 the US and China signed the Treaty of Wangxia, which was the American counterpart to the Treaty of Nanking. In addition to opening up Chinese markets to American traders, including the opium traders, this treaty also forced China to open itself up to American missionaries. As this NYT article from 1997 describes, one of the American merchants who benefitted from all this was Warren Delano. Delano made a fortune in the opium trade and returned to America in 1851. Later, through his daughter, Sara, he would become grandfather to FDR.

The Chinese learn of the unequal treaties in the wake of the opium wars (there was a 2nd opium war) marking the beginning of a century of the humiliation of a great civilization. And therein lies the irony. We supported the British in forcing China to open itself to the opium trade. We benefited from the humiliating treaties imposed on China in the wake of the opium wars. And now, we are trying to stop the flow of opioids from China. Today we Americans may think of our history with China going back only to Nixon’s groundbreaking visit to China in 1972. I suspect that’s not all that the Chinese remember.